The Mythic Beginnings (1967)

Walter Ego met The Get Quick in 1967 on the chaotic set of the Amerikan Wranglers TV series, where he was officially listed as Assistant Director—but in reality served as field commander, propaganda chief, and occasional emergency stunt double.

He shot on 16mm when told to use studio tape, brought in his own light filters, and reportedly wired the soundstage with directional mics stolen from a CIA drop in Tangier. The result? A TV show that felt like a military coup conducted by beat poets.

“I didn’t want to make TV,” he once barked to CineMag. “I wanted to disseminate telepathic landmines.”

Walter Ego immediately clashed with Erjk Vanderwolf, who insisted on performing all his own stunts, rewriting scenes mid-shoot, and walking around in character even during craft services.

They nearly came to blows during the “Robo-Rodeo” episode, and Ego later described Erjk as:

“A pain in the neck wrapped in leather pants and a god complex. But he bleeds on camera like a samurai. You don’t throw that away.”

The Early Collaborations (1968–1972)

After Amerikan Wranglers imploded under the weight of its own paranoid surrealism, Ego continued shooting unofficial TGQ promos—guerrilla footage projected behind live gigs, or slipped into BBC programming disguised as public service announcements.

One infamous short, “Death Rides a Harpsichord,” featured the band in fencing masks, performing in a public swimming pool haloed by fire. It was banned in five countries and won the 1969 Psychedelic Cannes Special Jury Prize (category: “Fanged Aesthetic”).

Mitch Joy, ever the realist and wary of the band following the decadent Hollywood decline of Elvis, resisted Ego’s intentions from the start.

“He wants to make us movie stars so he can write our obituaries. The Get Quick is the thing. The real thing. As real as my fist. I’m not interested in the dream factory.”

Yet even Mitch couldn’t argue with the cult buzz these short films generated. Bootlegs of Walter Ego’s TGQ Reels were passed around college campuses, war rooms, and fringe temples for decades, never losing their cult pop culture cache.

The Wreck of The Iron Dream (1998)

After years apart—and many failed attempts to mount a TGQ feature—Ego reemerged as Executive Producer on Ernesto Bellini’s The Iron Dream, billed as a surreal quasi-biopic/futurist alternate history parable action adventure epic romance.

It was a disaster.

Shot in abandoned metro stations under East Berlin, the production was plagued by all manner of insane SNAFUs. Erjk’s refusal to say lines as written, instead crafting his own dialog culled from the Nuremberg trials. Mitch Joy convincing the half of the backers to pull funding mid-shoot, citing “philosophical irrelevance.” Bellini having a nervous breakdown and shooting the final third with a pantyhose puppet that he claimed channeled the “real” Coco LeBree.

Ego mortgaged his house twice to keep the film alive. When it finally screened in Venice half the audience walked out in the first 20 minutes — but has since become regarded as an underground cult classic, dissected in think tanks, zines, and esoteric film circles. Many critics and pop scholars consider it to be a major, vital and groundbreaking influence on the tone and pacing of many subsequent highly acclaimed works.

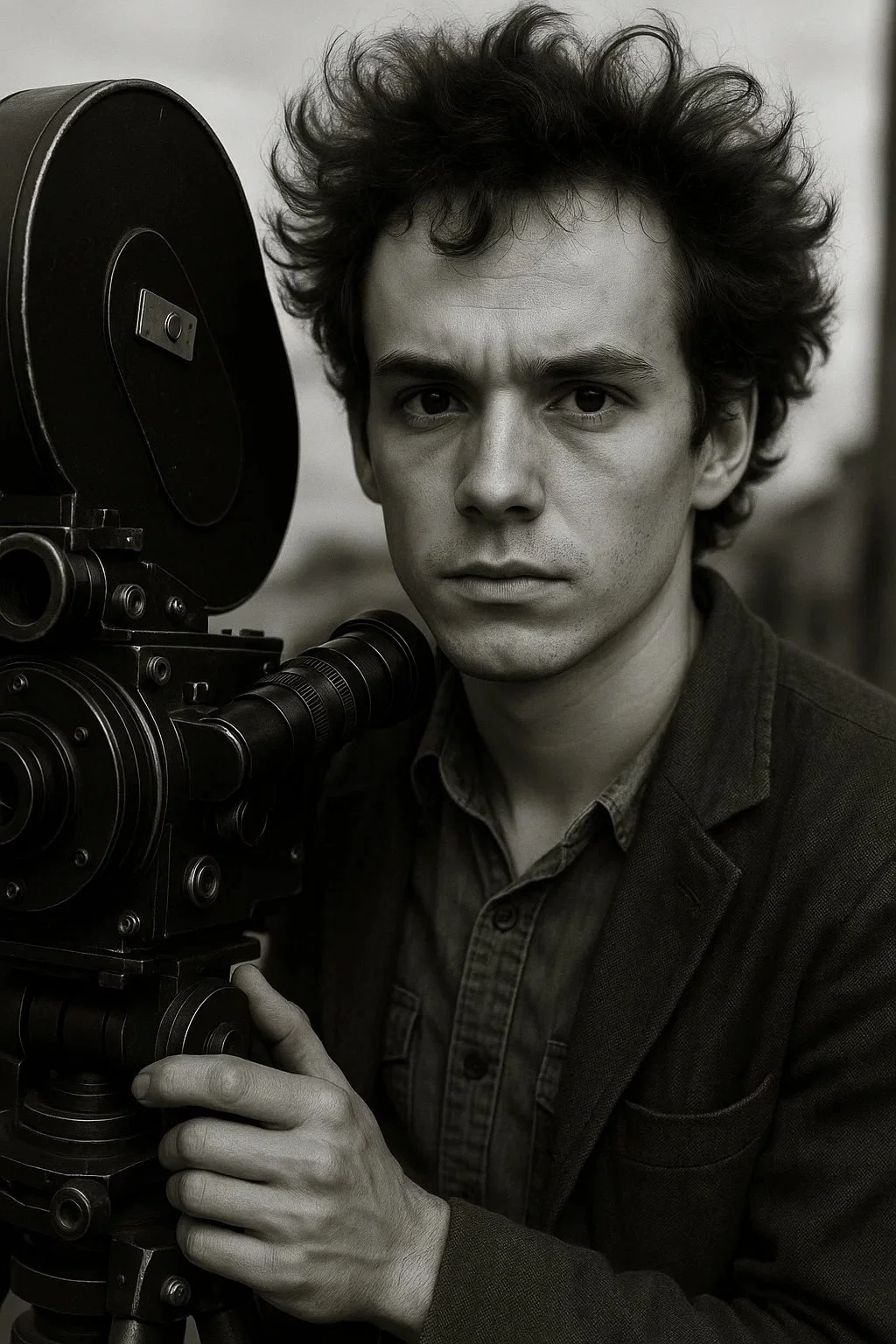

The Man Himself —

Walter Ego was known for carrying a .357. And a custom leather-bound notebook labeled “SHOTS TO DIE FOR.” Starting shoots with the phrase: “We’re making dreams with fists, boys. Don’t flinch.” Drinking “battery acid” — Wild Turkey spiked with a handful of buckshot and rock salt. Once editing an entire sequence blindfolded to “see if I could cut by gut.” He was a two-fisted maverick from a generation of man’s men. But he was also one of a kind.

His style never truly jibed with the band, but they were, nonetheless, of the same world—siblings of chaos. He called them “The Last Honest Myth.” They called him “The Ego Engine.”

The Late Reconciliation (2000s)

In the final years of his life, Walter Ego reconnected with Mitch and Erjk separately. There are reports of a joint commentary track recorded with Joy for a never-released DVD edition of The American Wranglers. And a drunken fireside conversation with Vanderwolf filmed in grainy infrared, where the two discuss art, death, and God’s absurd jealousy of jazz.

Ego died in 2012, heart attack during a midnight screening of The Get Quick: Live in Bucharest. Erjk Vanderwolf delivered a monologue at his memorial, while Mitch Joy, onstage before a back projection of Ego’s TGQ Reels, lit a Chesterfield and said:

“This [set] is for Walter Ego. He was a genius and a bastard and an angel. And he gave us something no one else could — permanence in a world that wanted us erased.”

— Mark Question, 2011