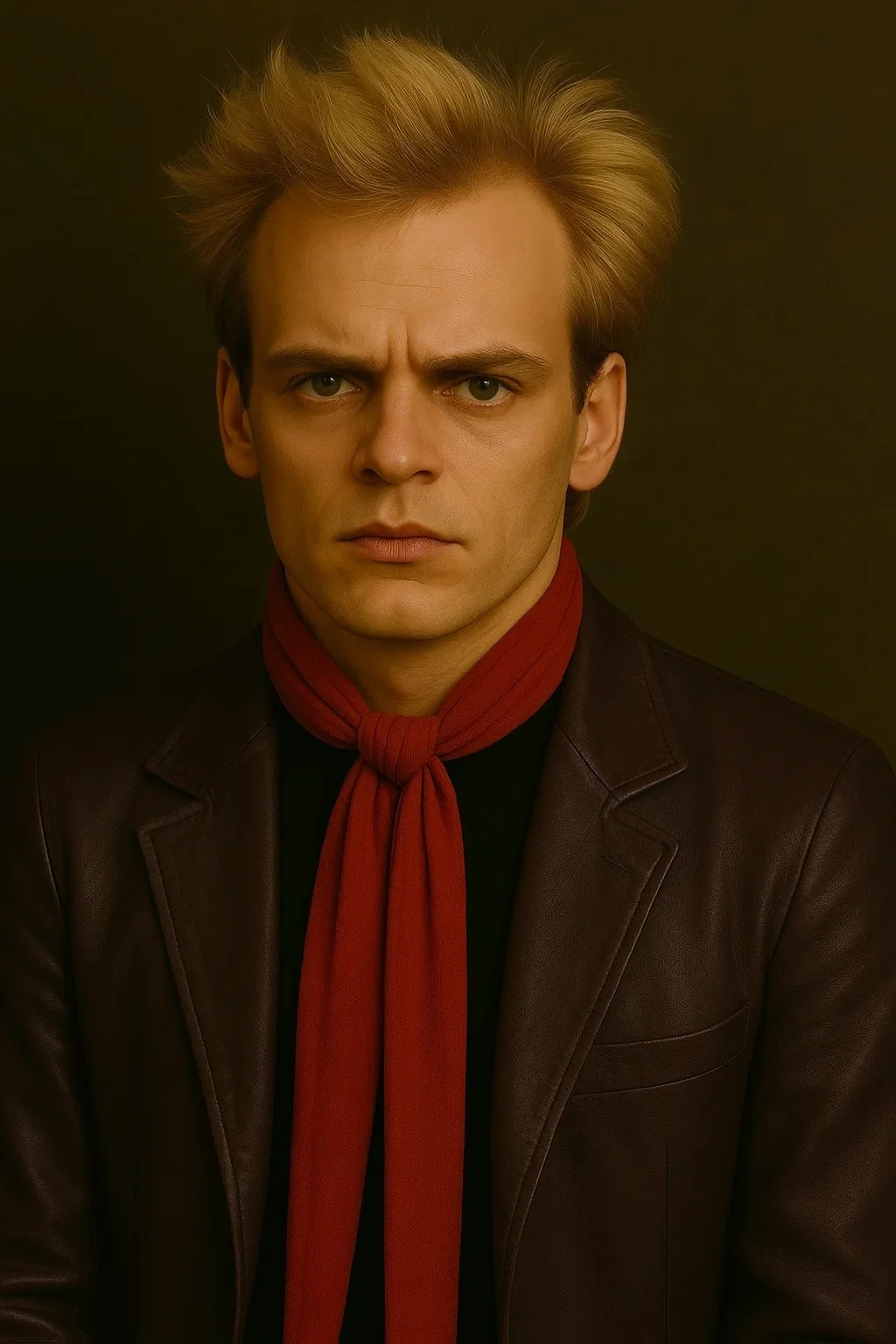

Architect of Silence. Designer of Error.

In a world increasingly ruled by noise, Klaus Vallis listens for the spaces in between.

Born beneath the cool, eternal gaze of the Matterhorn, Vallis seemed destined to live at high altitudes. A classically trained painter turned electronic sound theorist, his journey from avant-garde alpine hermit to one of the most influential musical minds of the digital age is the stuff of synthesizer folklore.

A founding member of the late-60s experimental art-rock collective Slip Hounds, Vallis quickly earned a reputation as an innovative bassist as well as the nickname “The Philosopher Stone” — known less for traditional low-end grooves and more for the eerie tectonic rumbles he conjured via filters, bowing techniques, and self-hacked oscillators. But it wasn’t long before he outgrew the band format and began his metamorphosis into a solo force.

His early 70s work — Crystal Lipstick, Stiletto Theory, and Bruised Gold — landed somewhere between sci-fi cabaret and glam techno-opera, each album a high-gloss hallucination built on modular madness and decadent theatricality. But it was 1982’s Matterhorn that redefined him — and arguably, electronic music itself.

One of the first commercially released albums created entirely using digital tape and a prototype Fairlight CMI, MATTERHORN was a frostbitten masterpiece. With its sampled Tibetan throat singers, reprogrammed wildlife field recordings, and pulsing undercurrents of ancient rhythms, it established the template for what Vallis termed “desert-drone” — a cinematic subgenre both desolate and devotional.

Fans didn’t just listen to MATTERHORN — they crawled inside and inhabited it.

Critics called it “a sonic language for dreamworlds in decline.”

From there, Vallis became a holographic beacon of modern music — appearing everywhere, but always just out of reach. He mentored a generation of sonic explorers like Hassan-i-Sabah, and dipped his elegantly gloved hands into the bubbling aquifers of avant-pop, co-producing Coco LeBree’s polarizing L.A. Trilogy and guiding the angular evolution of bands like The Precepts through the jagged currents of the post-punk Faux Wave scene.

He also coined one of the era’s most enigmatic studio principles:

THE DIVINE MISTAKE — “the perfect flaw that breaks the loop and opens the gate.”

In 1987, Vallis and long-time kindred spirit Stuart Kendrick were inducted into the world of The Get Quick, ushering in a decade-long golden age that fused analog excess with digital precision. Over 15 albums, Vallis sculpted sound like it was molten metal, crafting immersive, crystalline productions that felt at once ancient and ultramodern.

Outside the studio, Vallis explored everything from interactive visual installations to algorithmic lullabies. His newspaper column in The Op Preserver blurred journalism and speculative fiction, while his collaboration with artist Peter Whitney, Chants de Count Saint-Simon, produced a series of sublimely twisted books “for devious children and futuristic nostalgics.”

These days, Klaus Vallis maintains a low-profile orbit, appearing occasionally via encrypted video at symposiums on “anti-logic in digital systems,” or “the aesthetics of misfire.” Rumors swirl of a lost opera composed entirely for glass instruments and underwater speakers, or a final album encoded as a living genetic sequence.

Whatever the truth, one thing remains certain:

Wherever machines dream of ghosts, Klaus Vallis already has command of the digital echoes.

— Mark Question, 2007