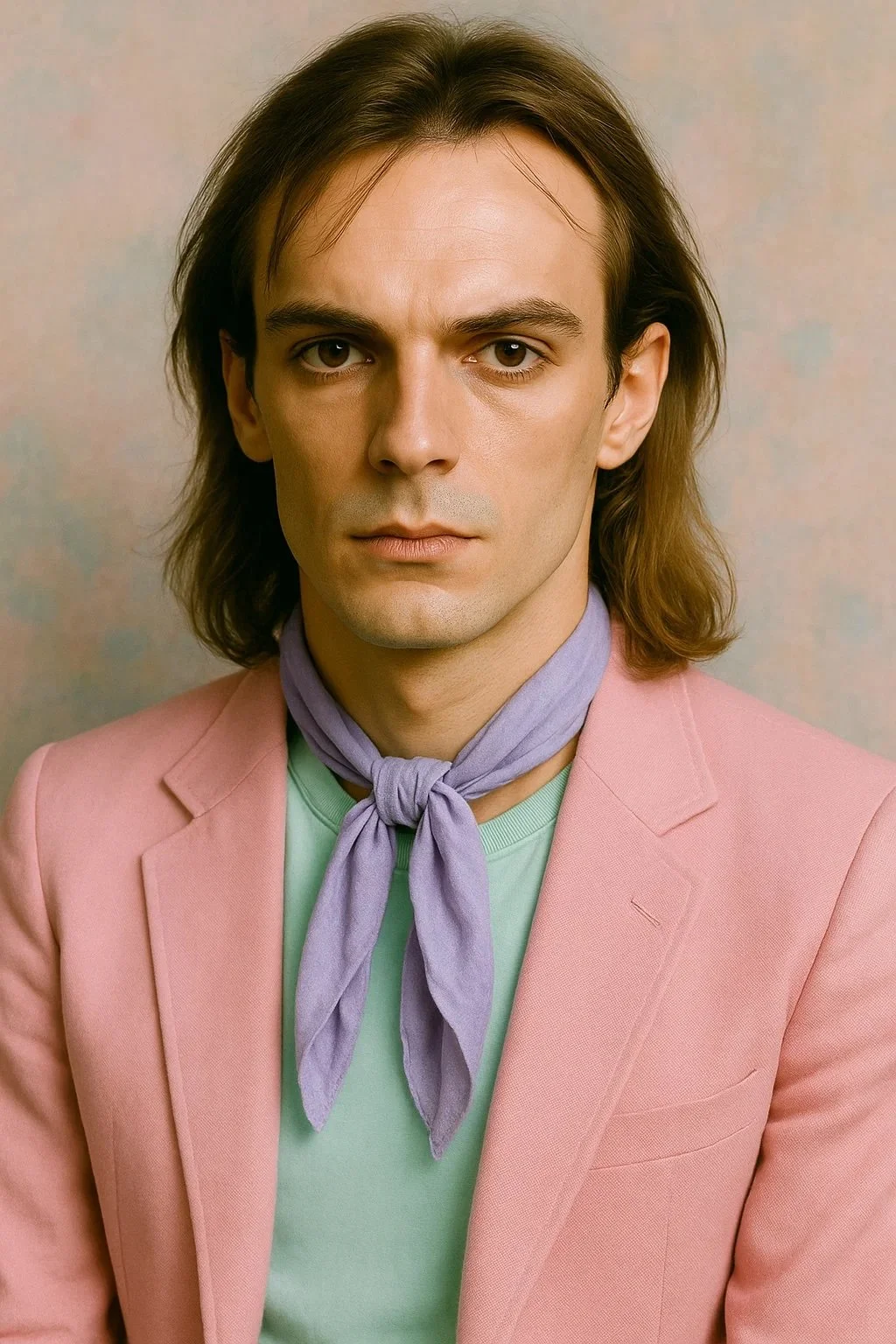

The Human Filter. The Sonic Architect. The Man With the VCS3.

If you ever wondered what it would sound like if the mind of Robert Fripp got trapped inside a Newton MessagePad during an anime lightening storm, you’re halfway to understanding Stuart Kendrick.

An avant-garde technologist disguised as a musician, Kendrick began his strange loop of a career not on stage or in a studio, but in the conceptual chaos of mid-1960s New York City. Fresh from University and burning with curiosity, he found himself seated beside fellow visionaries like Jan Hammer and John Cage in a durational descent into madness: the first complete 18-hour performance of Satie’s Vexations. It was a test of endurance, yes — but also a philosophical initiation.

Kendrick passed.

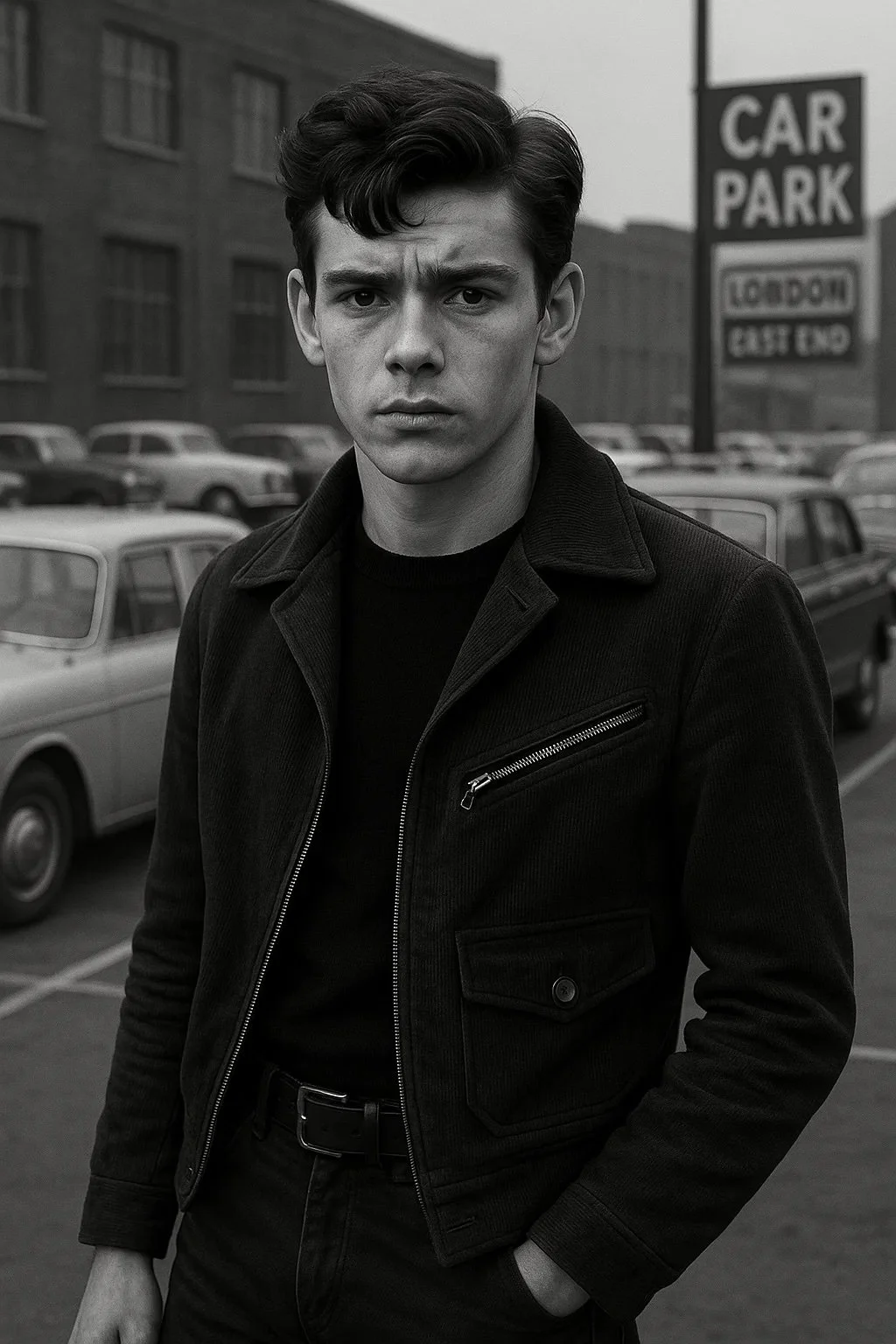

From there, he jumped into the psychedelic fray with Slip Hounds, a shape-shifting, feedback-forward noise unit founded with Klaus Vallis in a future-focused1965. But after three years of sonic friction and business static, Kendrick split — leaving the group and chasing something deeper: a music that reacts back.

By the early 1970s, Kendrick had become a central node in the Fluxus intermedia network, where he helped smuggle sound art into the gallery world and vice versa. He coined the term “elusive music” — ephemeral audio designed not to dominate a space, but to subtly recode the listener’s experience of it. Think ambient with an attitude, glitch before the glitch.

His solo work through the decade combined electronics, acoustic instruments, and algorithmic structures, often credited with predicting the rise of ambient techno and the early AI music experiments of the 1990s.

But it was in 1987, under highly unlikely circumstances, that Kendrick rejoined forces with Klaus Vallis — both men recruited by The Get Quick during a turbulent period of reinvention. Their shared brainwave frequency would prove vital. Stu, ever the sonic shapeshifter, became less a musician and more an operating system for the band’s live and studio output.

Behind the console, he ran bass lines through vintage echo units, sent guitars spiraling through VCS3 patch matrices, and spliced vocals like tape-era DNA. In interviews, he referred to himself as a “signal sculptor,” someone who didn’t play the band so much as refract it.

Live, he juggled guitars, synths, processors, custom mixers, and what fans swore was a modified Commodore 64. His rig looked more like a Cold War command center than a rock setup.

He stayed with The Get Quick for ten albums and a decade of phase-shifting evolution — before announcing, in a faxed press release that read more like a performance piece, that he was “disconnecting from the mainframe.”

Now splitting time between Edinburgh and Phoenix, Kendrick leads a lower-profile but no less fascinating existence, contributing essays and theoretical sonic essays to publications like ARTicle, Fractal Code, and the occasional obscure software zine. Rumors persist that he’s developing a music language composed entirely of sub-audible frequencies, or perhaps soundscapes that can only be performed backwards through time.

But as he once said in a rare 1993 interview:

“Some people play notes. I prefer to play context.”

— Mark Question, 2007